I am not a gamer by any stretch of the imagination, so this won’t be your typical video game review.

I don’t think so, anyway. Because I don’t read video game reviews, either.

A couple years ago I bought an Xbox One for the family. I used it for the Blu-Ray player and Pandora. The kids used it for Minecraft.

The idea that I would use it for gaming wasn’t too much on my radar.

Not that I haven’t played games before. I’m not a n00b, kidz. (Please do picture your friend’s dad saying this, preferably whilst throwing ‘signs’, yo.)

It’s just that … well, I’m sorta old. And my own previous video game loves were largely of two varieties. Back in my NES days, I loved Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which in my PC days morphed into an abiding love of Civ-style games (full-add-on Civ4 is my favorite). Alongside all that, though, I loved RPG-style games, like Neverwinter Nights and, more recently, Skyrim (where I am the legendary Khajiit archer, Mister Whiskers).

Alongside my casual interest in gaming, I got a history degree, a couple of Masters degrees, a PhD, and became a professor of medieval culture specializing largely in what might broadly be called War Studies. Also, I wrote The Shards of Heaven, a trilogy of historical fantasy novels set between the death of Caesar and the birth of Christ.

I mention all this as background, because one day a Shards fan asked me on Twitter if I’d played Assassin’s Creed Origins. It was set, I was told, in the same time period as my first novel, even featuring some of the same locations.

As it happens, though, my Xbox One came with a couple of Assassin’s Creed games: Black Flag and Unity. And, after thinking on the matter, I decided to try my hand at this sort of game. For, you know, research purposes.

Thus I started up Black Flag, and I became an assassin-pirate. As one does.

It turns out that I really like this kind of game. It appeals to the hidden-history and lost-artifacts kind of historical fantasy around which I built the Shards of Heaven novels, and I absolutely adored the fact that while there was certainly an element of hacking and slashing to the game, it was also … well, cerebral. I really enjoyed the patient work of infiltrating and clearing out a Spanish fortress without ever being seen.

Plus, you know, piracy.

I beat the game, but I didn’t forget why I’d tried it in the first place. A few days later, a sale at GameStop brought Assassin’s Creed Origins into my twitchy hands.

A couple weeks later, I’ve beat that game, too. Or, put more accurately, I’ve beaten the main story that threads through the open world of Cleopatra’s Egypt. My conclusion:

Oh my gods.

It is beautiful.

It is a blast.

I’m going to talk a fair bit in this review about the historical connections within the game, and, yeah, I might nitpick here and there about places where they erred. But I don’t want you to think for a minute that I didn’t like this game. I friggin’ loved it. And some of the historical connections they made were nothing short of breathtaking.

Part way through the game, for instance, your player character—a vengeful father named Bayek—has come into the employ of Cleopatra in the middle of the Egyptian civil war between her and her brother-husband. The writers did a great job, I thought, of explaining the fairly confusing political dynamics at play. And then—then—Cleopatra at one point dismisses you and your wife (a total badass named Aya) with this command: “If you find my brother … ginisthoi.”

I positively squealed in delight when the pharaoh said this.

I mean, for one thing, she’s friggin’ Cleopatra. But for another, well, it’s a bit of a story in its own right…

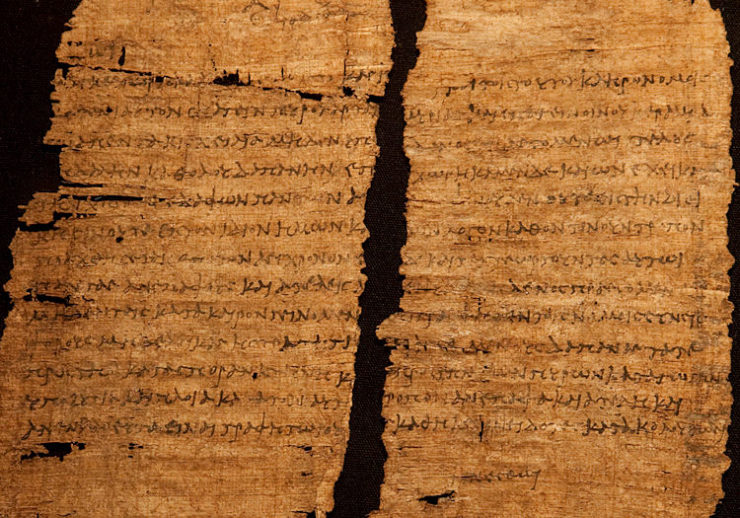

Berlin P 25 239 is the shelf name for a papyrus held by the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung in Berlin. It’s not a terribly exciting document at first glance: written in February 33 BCE, it grants a royal tax exemption to a Roman named Publius Canidius, who just happened to be a good friend to Cleopatra’s Roman lover, Mark Antony. It’s a simple bit of administrative business, hardly worth a second glance…until you notice a single Greek word that someone has added at the bottom of it. That word—ginisthoi, which means “make it so”—on this kind of document at this time in this place could only reasonably have been added by one person: Cleopatra herself.

I know! History is so cool.

In fact, I thought this obscure bit of papyrology was so cool that I slipped an Easter egg (one of hundreds) into the Shards trilogy that would refer to it. Here’s a passage from chapter 10 of the first book, in which Roman legionnaire Lucius Vorenus has woken up in what passes for a hospital in Alexandria, where he talks with his good friend Titus Pullo and Caesarion, the son of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar:

“You said something about me getting better ‘in time,’” Vorenus said.

“So I did.” Caesarion spoke with a smile, but the look in his eyes was grim.

“In time for what?”

“To take a ship,” Caesarion replied.

“A ship?”

“A ship north,” Pullo said. Any trace of a smile on his face was gone.

North. That could mean only one thing. “War,” Vorenus said quietly. “And Egypt?”

“My mother is going herself,” Caesarion said. “I’m to stay here in Alexandria in her absence.”

“Cleopatra herself?”

“Antony didn’t want her to go, you know,” Pullo said. “But Publius Canidius convinced him to let her. I think he must have owed her a favor or something, and she called it in. She’s taking the whole fleet, Vorenus.”

Most readers, I suspect, probably figured I made up the name Publius Canidius just to name some random Roman. But even among those who recognized that he’s in fact as historical as Pullo and Vorenus (and of course Caesarion himself), I cannot imagine many made the connection that the “favor” he owed Cleopatra was, in all likelihood, the royal tax exemption she’d granted him the previous year with that simple word: ginisthoi.

So, yeah, I truly squealed when I realized that the game designers for Assassin’s Creed Origins had done much the same with an Easter egg of their own: they took that Greek word and put it in Cleopatra’s mouth as part of the order to take out her brother. Ginisthoi!

As astonished as I was by the extraordinary realism of the graphics in general—from stunning Egyptian vistas to the smooth movements of Bayek’s garments—it was this kind of attention to historical intricacy that blew me away again and again.

Let’s take a look at Alexandria, for example.

The city was founded in 331 BCE by none other than Alexander the Great, and it was one of the first massive cities to be truly planned and engineered. Three hundred years later, around the time of Cleopatra, it was a wonder of its age—quite literally, in fact, since its harbor boasted the Great Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Alas, on 21 July 365 a massive tsunami (triggered by an earthquake on the island of Crete) struck the city. Buildings were leveled, and much of the great harbor and its royal palaces and monuments sank beneath the waves. The passing centuries did even more damage, as the expansion of the city and the forces of both nature and man progressively eradicated the city of Cleopatra.

Today, to imagine ancient Alexandria we have two points of certain reference on land. The first is Saad Zaghloul, a small public park where the so-called Cleopatra’s Needles once stood (the obelisks themselves are now in London and New York). These monuments, we know, once stood in front of the Caesareum, which we can thus fix in place. The second point of reference is the misnamed Pompey’s Column, on the opposite side of the ancient city. This marks the site of the Serapeum, a large temple to Serapis in Cleopatra’s day.

And that’s pretty much it. We have good reason to think that a couple of the main streets in modern Alexandria more or less follow the course of the two biggest streets in the ancient city, but even that doesn’t tell us much.

The designers of Assassin’s Creed Origins thus had a major task on their hands: they needed to re-construct one of the most important cities in the world, of which precious little remains.

I know their pain. In writing The Shards of Heaven, I did the very same thing. And the more research I did, the more frustrated the picture of the ancient city became. No one, it seemed, had taken into account all the evidence we had at hand. No one had produced what I needed: a reasonably accurate map of Cleopatra’s Alexandria.

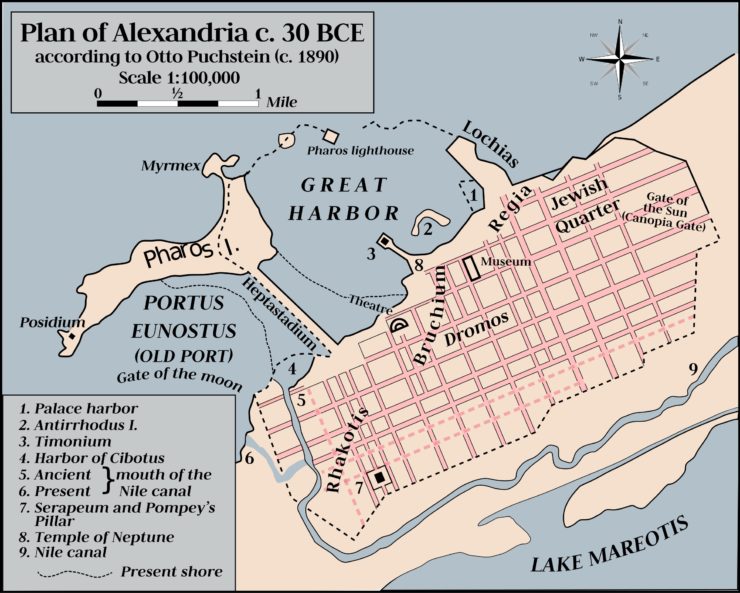

There had been attempts, of course, which were based on what little physical ruins remain in the city, combined with the descriptions of recorded visits to it—like that of the ancient geographer, Strabo. Many of these attempts are collected on this website dedicated to the search for the body of Alexander the Great. But all of these maps had clear and significant errors—like this one from Wikipedia:

What made most of these maps wrong was their incorrect idea of what the ancient harbor looked like. It had sunk beneath the waves in 365, you recall, and early on some scholars just made a wild-ass guess about what it must have been like—a blind flail that was then repeated so often folks thought it was the genuine reality.

Until somebody looked at it.

It’s astonishing how often this happens in scholarship. Old ideas are given credit because they have been so long held that, well, they have to be true, right?

Certainly not in this case. Beginning in 1992, underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio began systematically surveying Alexandria’s harbor. What he found was that it had little in common with what folks thought. He also found a host of remarkable treasures, including the head of a statue believed to be of Caesarion—the son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra who happens to be a main character in The Shards of Heaven and also makes it into a clever cut-scene in Assassin’s Creed Origins:

Anyway, as I was unable to find a map suitable for my purposes, I made my own.

Anyone who has watched my career knows that I really enjoy detective work like this. Was Alexander’s tomb beneath the mosque of Nebi Daniel? Or near the Attarine mosque? Or was it where St. Mark’s is now? Or somewhere else—closer to the royal palaces on the Lochian peninsula, perhaps? And what of the Great Library? It’s long thought to have been near Alexander’s mausoleum, but in 2004 archaeologists uncovered lecture halls up near Lochias (near where the modern Alexandrian Library is located).

To make things simpler for myself, I took an existing reconstruction of the city and revised it to take into account the findings of Goddio and a number of other issues. I posted this map to my website in February 2008, noting that it still had issues but seemed better than anything else out there.

It is now the number one hit on Google Images for “map of ancient Alexandria,” and it has been featured in Ancient Egypt Magazine.

As I said when I posted it, though, this map still isn’t right. I had many problems with it that I didn’t have time to incorporate.

That changed when Paul Stevens, then my editor at Tor (and now my agent extraordinaire), informed me that The Shards of Heaven would feature not one but two historical maps, and that I needed to provide “map scraps” to aid in the work of the cartographer, Rhys Davies.

What I sent in reply was this:

That this is what he was sent makes it all the more impressive what Rhys Davies made of it (buy the book and see it!).

So what about Assassin’s Creed Origins?

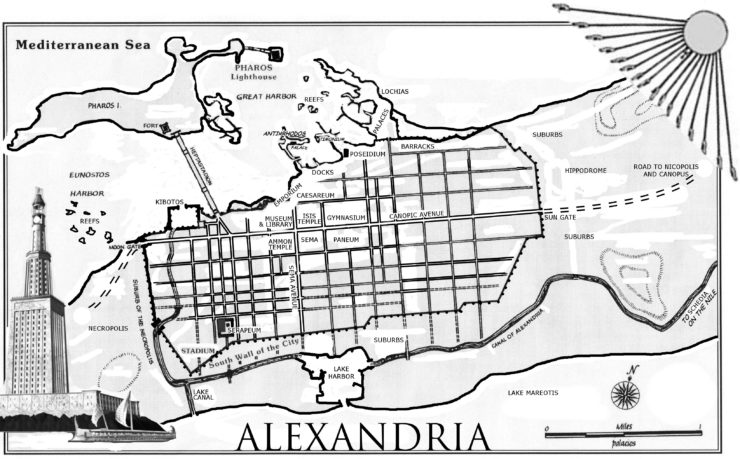

As you can see, they did their homework. Most notably, they’ve fixed the glaring error in the traditional maps of Alexandria: the location of the island of Antirrhodos in the middle of the Great Harbor.

No, not everything is accurate. For gaming reasons things are a bit wacky in terms of scale—their Antirrhodos is bigger than it ought to be relative to the harbor, and the city itself is very much squished in general—and I don’t know what they were thinking with the placement of the watercourses in the city and the shoreline of Lake Mareotis here.

But, seriously, the bigger picture is how much of this they bothered to get right.

Nor is this righteous rightness in place only at this macro level of mapping. Running through the streets of Alexandria shows an attention to detail at a micro level, too. Egyptians exclaim in Egyptian. Greeks grumble in Greek. Romans (when they show up) laud in Latin. The trees whistle in the wind.

And the architecture!

There’s a sequence in which you have to go into the Great Library of Alexandria. Constructed under the orders of Ptolemy I Soter (Alexander the Great’s general, who succeeded him in ruling Egypt) and organized under the direction of Demetrius Phalereus (who had been a student of Aristotle), the Great Library was the single greatest repository of knowledge for some three centuries—and we have little idea what it looked like. A number of sequences in The Shards of Heaven take place within or around its walls—a librarian at the time, Didymus Chalcenterus, is a main character—so I spent a lot of time reconstructing my own vision for the building.

The Library of Alexandria in Assassin’s Creed Origins doesn’t match my plan, but I can see exactly how they spliced the shards of history to fashion their own.

Behold! It has papyrus scroll shelves and all!

Seriously, I spent half my time playing the game and the other half wandering like a wide-eyed tourist. Did I visit the Serapeum? Sure did! The hippodrome east of the city? Been there, raced in it. Alexander the Great’s Tomb? Yes indeed.

Again, I can nitpick their reconstructions—Alexander’s sarcophagus probably shouldn’t be underground, Egyptian in its trappings, and filled with honey—but I can see why they made these choices. And more than anything I’m stunned to see someone else’s vision of the things I’ve spent so much time imagining in my head.

Plus, the world of Assassin’s Creed Origins ranges across the kingdom, tracing a story that threads beautifully through a civil war that’s layered atop social strife between Native Egyptians and Ptolemaic Greeks at a time when Romans are making their own incursions into the country.

And I’ve not even begun to talk about Memphis, the Pyramids, and all the rest of the extraordinary places you get to visit in this game.

In sum, I loved every minute I played—as a player, as a historian, and as a writer.

I can only hope the wait isn’t too long until the next entry in the series. And if y’all are needing ideas for that, Ubisoft folks, hit me up. Seems like there’s some killer fun to be had in the Hundred Years War. I got ideas.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.